Central bankers have prided themselves on clear communication with markets in recent years. But the road mapped out by Bank of England (BoE) policymakers isn’t taking UK interest rates where markets expected, leaving currency investors all at sea.

The BoE’s tone in later summer was hawkish, leaving few in doubt it was planning to raise rates to combat an inflation rate heading for levels last seen a decade ago. But that communication has yet to translate into higher interest rates.

At the bank’s November meeting, monetary policy committee (MPC) members struggled to make up their minds in what one called the most challenging monetary policy environment in memory.

Among the results of this indecision was the slowing of the pound sterling’s 19-month upward trend against a currency on the other side of the Brexit divide, the struggling euro.

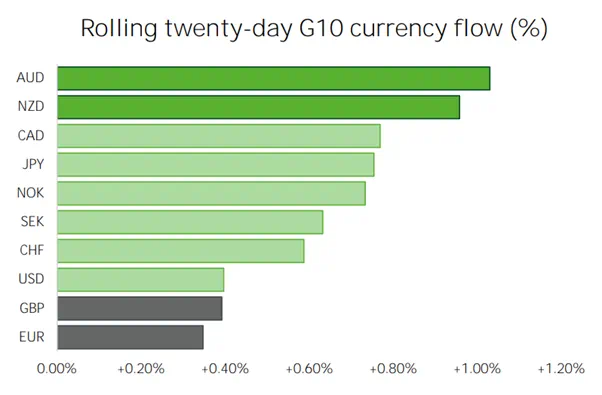

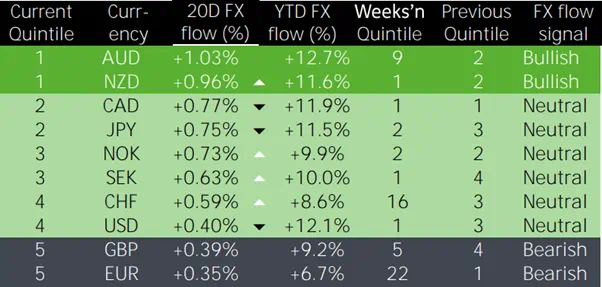

A recent EPFR data pull shows the euro and the pound (GBP) are currently both unloved and received the lowest flows of the G10 currencies over the 20 days ending December 1.

The euro has languished in the fifth quintile for flows over 22 weeks, but the pound has joined it there in the last five weeks.

Policy divergence…

After a post-Brexit vote slump, the pound’s relative revival against the euro was mainly due to the BoE’s policy divergence from the European Central Bank (ECB) as the UK’s central bank raised expectations of an early rate hike.

The market had expected the first increase this December or earlier. However, the onset of the omicron Covid variant delayed the decision and reduced expectations of a rate rise at the bank’s next meeting on 16 December.

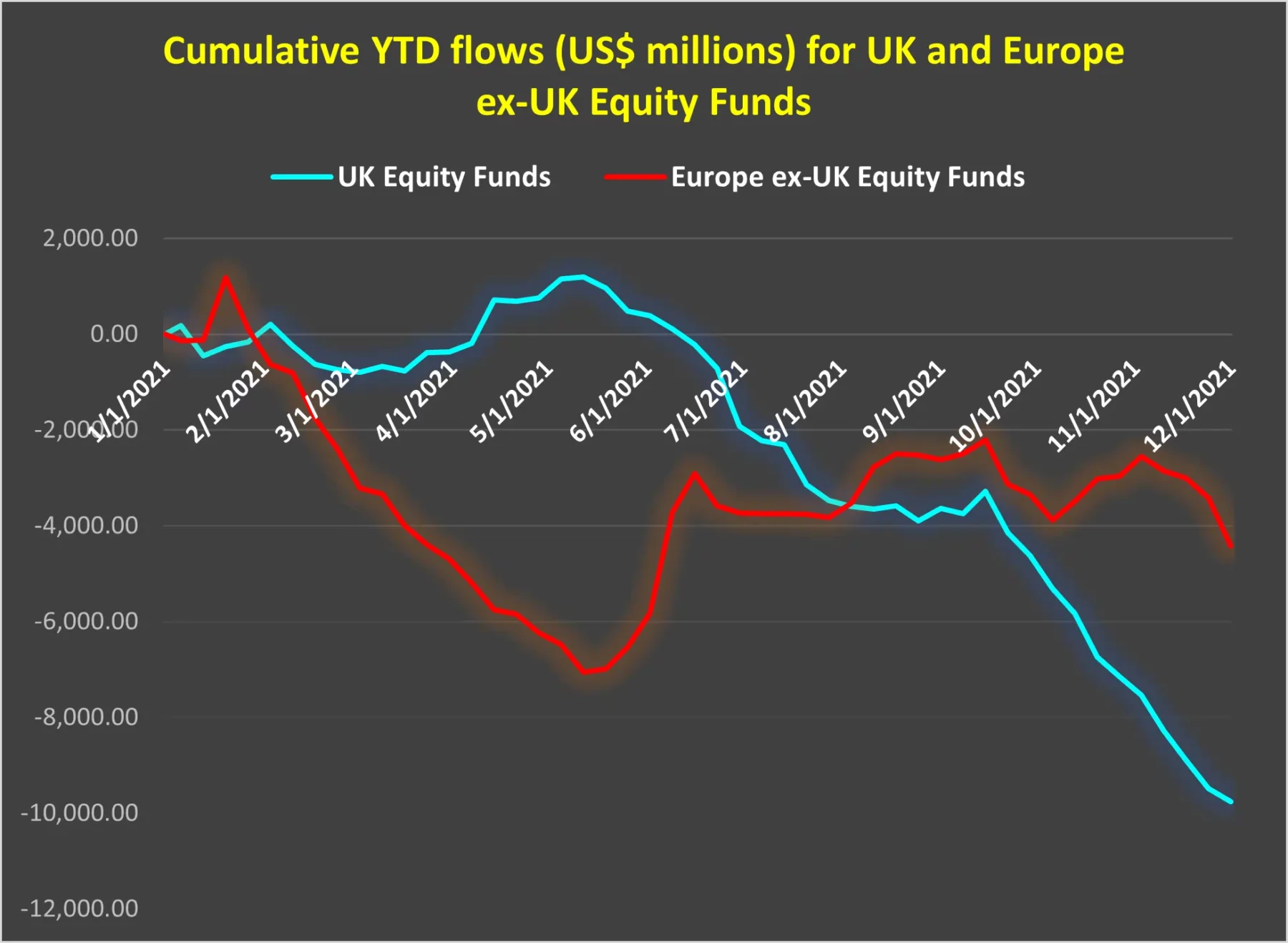

The bank’s emergency attempts to pump money into the economy during Covid were successful. Earlier this year, the dedicated UK Equity Funds tracked by EPFR were attracting more money than the Europe ex-UK Equity Fund counterparts. But the UK has not been immune to the economic headwinds sweeping across the continent.

Britain is currently wrestling with a tough matrix of interconnected problems, including Brexit, Covid and soaring inflation led by runaway energy prices. These have been made worse by suppliers struggling to meet huge pent-up demand, post-lockdown, and the avalanche of new rules and tariffs faced by traders after Britain’s exit from the European Union.

…and currency convergence

Advocates of the UK’s departure from the EU anticipated the freedom to craft a nimble economy marked by lower taxation and lighter regulation. Success, they expected, would manifest itself in many ways, with one of the scorecards being the GBP’s popularity versus the euro. That both would be propping up the bottom of FX models was not part of that vision.

But the cost of dealing with the Covid pandemic and the scale of post-Brexit trade friction continues to make the hoped-for outcomes highly uncertain. Concerns about a trade war between the UK and the EU have intensified in the last few weeks, heaping more pressure on the GBP and slowing its resurgence.

Though the UK congratulated itself on its response to Covid earlier this year, that pride has evaporated as other countries caught up with their vaccination programs and the omicron variant brought fresh fears.

Meanwhile, the UK’s consumer price index surged to a 10-year high of 4.2% in November. The BoE expects it to peak at around 5% in April 2022. Sharp energy price rises and the emergence of the omicron variant also affect the eurozone, of course, and inflation has surged there too. But the policy context is different.

Europe is less affected by Brexit than the UK. But the ECB also believes monetary policy has been too tight since 2010, and it has updated its framework to allow price rises to go above 2%. In contrast, the BoE has not revised its 2% target, so it has less wiggle room.

Biting the hand that fed it

Expectations of a rate rise surged after a speech on 17 October by BoE Governor Andrew Bailey, during which he said “we will have to act” in response to medium-term inflation expectations. However, he and other MPC hawks changed their minds in November as the potential threat of an omicron-fuelled wave of the pandemic grew.

If MPC members’ current comments are to be believed, it will continue with its plan to hike rates in the new year.

But there is another factor adding to the confusion. That is the unwillingness of the BOE to abandon its “transitory” narrative when it comes to inflation. The bank still insists inflationary pressures – to which their highly accommodative polices have arguably contributed to — will fade into the summer of 2022.

Some investors believe central banks have no choice but to say inflation is transitory because, if they don’t, it will fuel expectations further and become self-fulfilling. If that is true, we should take everything central banks say with a large pinch of salt.

But it’s a frustrating game to play when there are such large potential repercussions. Delaying a rate hike could embed inflation deeper into the economy as workers demand more wages to meet household bills, creating an upward spiral.

This has started already with UK supermarket workers striking in the run up to Christmas, describing a 4% pay rise offer as a “real terms cut”. Overall wage inflation is at its highest level for 14 years, though it is hard to read too deeply into those figures, given the ending of the furlough scheme in September.

After a decade of ultra-low rates, the BoE is itching to raise them to keep inflation at bay and restock its arsenal ready for the next crisis. Many investors would support that — but only if it is orderly and well-communicated. Recent FX data suggests otherwise.

Did you find this useful? Get our EPFR Insights delivered to your inbox.