Changing interest rate cycles are often associated with market volatility and dislocation. This time is no different with investors responding erratically to the news that the long-expected phase of rate hiking has begun.

It is a complicated picture as policymakers struggle against multiple morphing foes, like a hydra that grows back two heads each time they chop one off.

Economists have decided that higher prices are the biggest threat – even while the omicron variant continues to rip through populations, forcing several countries to bring back restrictions and lockdowns.

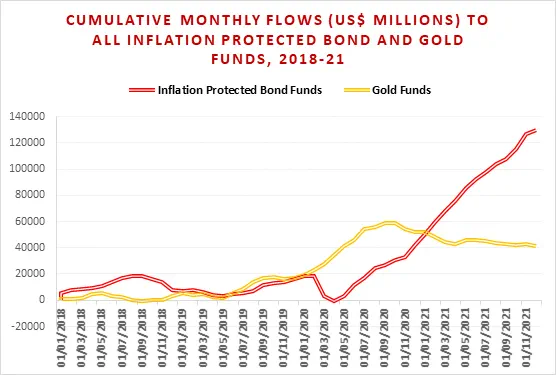

Through the second half of 2020 and well into 2021, policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic insisted inflation would prove transitory in the face of mounting news about unexpectedly high price rises. It was a story that investors weren’t buying. Flows to the Inflation Protected Bond Funds tracked by EPFR took off in 2Q20 and kept on climbing.

But as inflation hit multi-decade highs in December, the central banks were forced to change their tune and slam on the economic brakes.

The Bank of England was the first to move, with a rate rise in December. This followed the US Federal Reserve’s December policy meeting, in which it signalled up to three rate hikes in 2022.

Credibility regained…

Not surprisingly, the Fed’s signalling had an immediate impact on flows into real estate and fixed income fund groups during mid-December. Global, emerging, and short-term bond funds all posted outflows. Among the worst hit were US bond funds, which experienced their heaviest redemptions since Q1 2020.

But flows swiftly regained their equilibrium. In some cases, they never wobbled. During the first week of 2022, Europe Bond Funds chalked up their fourth straight inflow ahead of the news that Eurozone inflation hit a record high in December.

Among the explanations for this are the credibility central banks have regained by acknowledging the obvious and the hope that inflation, while likely to be higher for longer, will tail off in 2023.

In the latest OECD forecast, global inflation is predicted to already be at its peak at around 5.21% and will gradually fall next year and level off at around 3% in 2023 – higher than in the previous decade but less troubling than current figures.

Inflation in the Eurozone will follow a similar trajectory, levelling off at around 1.75% in 2023, said the OECD.

…or the calm before the storm?

But is the OECD forecast right? Higher prices have been driven by a many-headed beast that includes pent-up demand, labour market shortages, disrupted supply chains, and a global strain on energy supplies. Bad weather conditions have been blamed for the latter but many suspect geo-political manoeuvrings by Russia to be an underlying factor.

Covid-related supply chain jams are still serious, and some analysts say they could worsen before they improve. A significant worry is that inventory-to-sales ratios hit record lows in 2021, and continued their downward trajectory through October, showing supply issues are far from resolved.

Some argue supply shortages are rarely long-term and should normalize through 2022, but we are still in unchartered economic territory. While some supply bottlenecks are easing, others are just starting. With omicron lockdowns and tighter controls such as vaccine passports for truckers still causing havoc, a return to normal supply chains could be some time away.

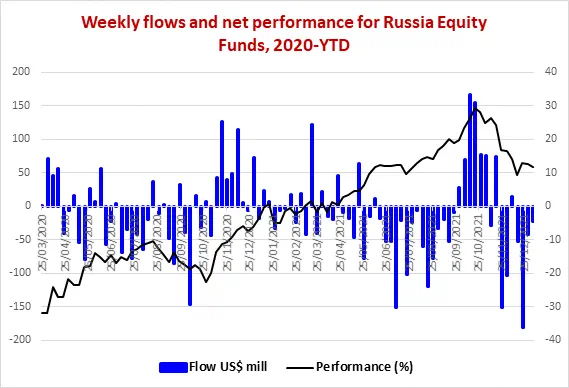

Poor weather will normalize at some point and natural gas prices are falling already. But relations with Russia could stay frosty for much longer, especially with Putin amassing forces on the border with Ukraine. Investors are not sanguine that Russia will be part of the solution rather than a big part of the problem.

Meanwhile, hard-to-fill vacancies are still on the up in Europe and America. Wage growth is falling further behind inflation, and workers are demanding higher pay to keep up with price rises.

The market consensus now is that the OECD’s analysis is too optimistic, and the peak of inflation is a few months off – especially since early Omicron data suggests its impact may be milder than expected, which would support continued economic expansion.

Alongside falling gas prices, the only solid data supporting a fall in inflation is household saving rates, which are dwindling and reducing pent-up demand as a factor.

Emerging dangers

With this backdrop, several dangers are emerging. One is that, despite the above, inflation is nearing its peak already, meaning the Fed’s planned three rate hikes next year could be too aggressive and cause unnecessary damage to a still fragile post-Covid recovery. This is perhaps the least worrying as the Fed could soon soften its policy if needed.

Of greater concern is the prospect of inflation becoming embedded in US, European and other economies as workers seek higher wages to compensate for their fall in real value, creating a vicious cycle of rising prices.

The worst-case scenario is stagflation, where prices keep rising but economic growth does not. That appears to have been the case in Germany late last year, with price growth at a 29-year high while overall GDP growth slowed to a crawl.

Furthermore, the new cycle signals the day of reckoning for quantitative easing and the looser monetary policy that has kept markets buoyed for the last decade and more. No one yet knows what effect this tightening could have, but the 2013-14 ‘taper tantrum’ is still fresh in many minds.

As we move into 2022, markets and policymakers can only hope omicron signals a milder phase of Covid and the hydra can wind that neck in, while they start controlling inflation in a more orderly manner.

Did you find this useful? Get our EPFR Insights delivered to your inbox.