Markets have reacted coolly to Shell’s attempts to win over critics by simplifying its structure and moving headquarters from the Netherlands to the UK. The move takes one of the world’s largest private oil companies around, over – and, possibly, into – some of the major fault lines in Europe’s economic landscape: high versus low taxation, the pace of change needed to meet key climate goals, and the UK versus the European Union voted to leave.

The energy giant wants to prove it can keep rewarding shareholders generously while also shifting from fossil fuels towards renewables. It claimed the UK move, announced in November, would help achieve both by helping it return more cash to shareholders and speed up clean energy projects.

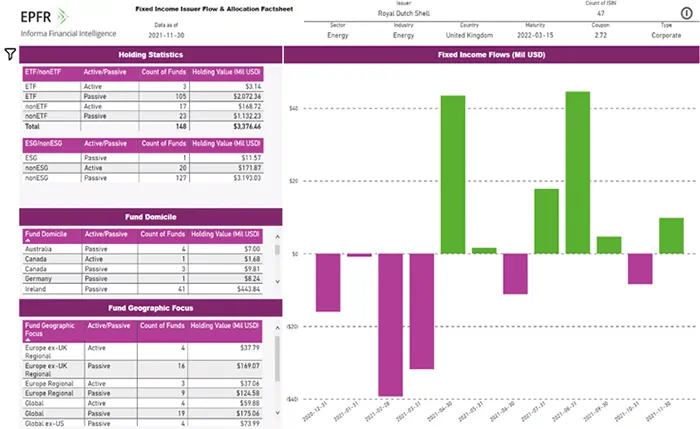

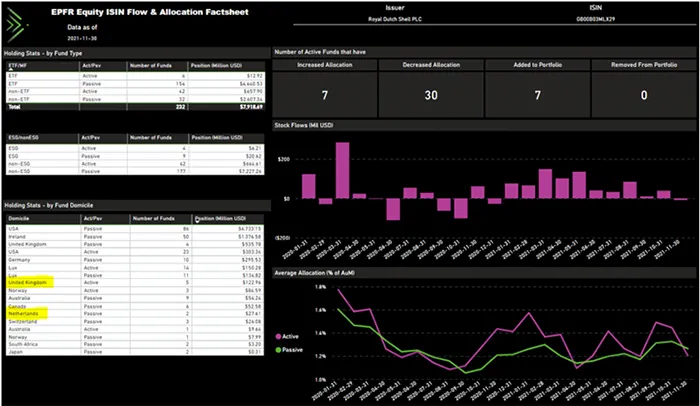

But according to EPFR’s Stock Flows and Fixed Income Flows and Holdings datasets, November’s equity flows into Shell turned negative for the first time in 2021. In contrast, fixed income investors appeared more receptive to the move, with modest inflows to Shell’s corporate bonds during November after an up-and-down year.

Shell has since moved quickly to convince investors its UK move can work. Changing its tax domicile avoids the Netherlands’ 15% dividend tax, which restricted buybacks to UK shares. Shell can now return shares quickly – and, in January, it announced an acceleration of its $7 billion share buyback scheme, using money from $9.5 billion of US oil and gas asset sales.

Shell also indicated it would invest at least some of the $2.5 billion remainder in renewable energies. It also highlighted that buying back shares reduces its dividend burden, potentially freeing cash for more such projects.

So far, so low hanging fruit.

Bridging walk and talk

Convincing investors it can transform into a profitable clean energy producer will be harder.

Shell’s daily production still averages over a million barrels of oil, a product whose price recently hit $90 as supply and demand mismatches continue to bite. The company estimates its oil production will only decline very gradually over the next 30 years.

So, it is under pressure to keep the fossil fuelled wheels of the global economy turning while remaining under fire from the environmental, social and governance (ESG) community. It remains unpopular with ESG mutual funds, and the November announcement was not enough to move the dial on this. According to EPFR data, only 13 ESG equity funds held the stock going into December compared to 119 non-ESG funds. And in fixed income, only one ESG fund held Shell, compared to 147 non-ESG funds.

Shell says simplifying its structure will increase its ability to reorganise; and buy and sell assets and acquisition targets to help accelerate its green transition. The group has already injected billions of euros into developing clean energies. But critics say it still has one of the biggest gaps between its environmental walk and its talk.

Where’s the value proposition?

While a simpler structure could help Shell develop more clean energy, it could also help the company maintain gas and oil production. In a frank interview published on Shell’s website in January, CEO Ben van Beurden made clear the company needs to keep pumping fossil fuels to stay liquid and fund green energy projects.

But activist investors say this twin strategy is muddled and breaking Shell into separate businesses would enable a sharper focus.

Shell’s share price rose around 12% between its November announcement and late January – mainly on the back of soaring natural gas prices.

But van Beurden believes misunderstanding about his dual approach means its shares are still undervalued.

‘Investors value companies that produce lots of surplus cash and dividends,’ he said. ‘They also value companies that do not generate surplus cash but have great promise, such as electric car makers. We are trying to mix both these models.’

Long-term, investors will be searching forensically for evidence that he is right or wrong.

UK says “f*** business”? Not this time

As Shell is one of the largest energy providers in the world, its move to the UK generated much speculation about wider economic impacts, post-Brexit as the UK’s departure from the EU is commonly referred to.

Some British commentators claim that, since the move is mainly about avoiding the Dutch dividend tax, it simply represents sensible accounting and does not amount to a vote of confidence in the UK.

But other factors are at play. Emission cuts have been forced upon Shell by a 2021 Dutch court ruling to nearly halve its total CO2 emissions by 2030. Van Beurden called the ruling a body blow, saying it made no sense to force companies to cut emissions while most people still rely on oil and gas.

Meanwhile, Dutch pension fund ABP – one of the world’s largest – plans to divest fossil fuel companies by 2023. In contrast, none of the UK’s largest pension funds have credible plans for such divestment, according to a Friends of the Earth report.

Most large investment bodies in the UK favour engagement with fossil fuel providers, though some are starting to insist on harder, faster emission cuts. But, all things considered, van Beurden does think the UK is a more competitive place to continue producing oil and gas as well as green energies.

Did you find this useful? Get our EPFR Insights delivered to your inbox.